Published on Wednesday, 14 Sep, 2016

Pokémon Privilege

Earlier this year I was in London, discussing Pokémon Go with a colleague. The game wasn’t officially out in the UK but had already flooded our social media channels, and I was adamant that I wasn’t going to get involved. It wasn’t a good idea. I have certain compulsive tendencies around collecting within games, and after I’d finally weaned myself off the Lego series (smash everything, collect all the studs, 100% the games), I decided that I really, probably shouldn’t start trying to Catch ‘Em All.

Fast-forward to the official launch and I’m again in London. Inevitably and predictably I cave to the hype and end up downloading it. That first day was a heady haze of constant Pokéstops, lures, and stumbling across rare creatures without meaning to. My boyfriend and I took an hour to walk what ordinarily takes 15 minutes, rapidly becoming those people who suddenly stop dead in the street. On returning home after the weekend I’d levelled substantially, and had already filled my in-game item bag with more Pokéballs than I thought I could ever use. Back in rural Suffolk however, absolutely nothing was showing up to use the bountiful supplies on. I needed to adjust to my new gameplay experience. I definitely wasn’t in Kansas any more. (There are lots of Pokémon there, I’ve checked).

Access to the internet is a given

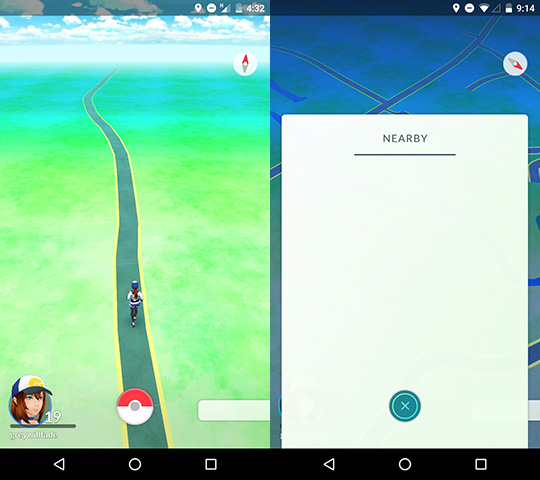

Outside of the lack of creatures popping up, I quickly realised that day-to-day, I couldn’t play. My home, where there is wifi, is not a spawn point for creatures to catch. Occasionally something will pop up on the ‘nearby radar’ as being somewhere close, however our village is in a valley and has absolutely no mobile phone signal whatsoever, meaning that it’s fruitless attempting to go hunting.

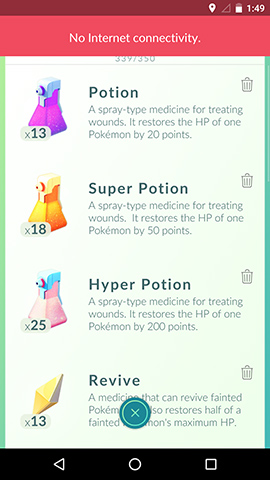

As the game requires data and GPS to run, without these you’re unable to progress past the splash screen, or actually do anything in-app (to the extent that you’re unable to even scroll a page of your previously caught Pokemon/items, or even close the overlay and return to the main map without an internet connection), meaning that any rare creatures that popped up just outside of my pool of home wifi would remain tantalisingly close yet un-caught. This limitation also affects another of the game’s core mechanics – the ability to catch creatures via ‘hatching eggs’. Eggs (along with other items such as Pokéballs) can be gained from Pokéstops – real-world points of interest dictated by the game developers and previous crowd-sourced knowledge – and once put in an in-app incubator the egg will hatch once you have walked a certain distance. Without any data, I couldn’t hatch eggs walking down my garden, to the village pub, or on longer walks. It started to feel like I was being excluded through my circumstances.

Exclusion

But I’m not alone. This feeling hit home even more when a young family member told me how she’d run out of Pokéballs (the sole means to catch creatures in the wild) as there were no Pokéstops even remotely nearby her to replenish her supplies. She marvelled at how many items I had, saying that she’d need to buy some (with real money) if she wanted to keep playing and keep up with her school friends, who all lived in a large town with Stops nearby. Not only did I have the mature adult ability/freedom to travel to the bountiful land of London to re-stock every now and again, I was arguably more likely to be able to aim more precision throws than her child-hands could, meaning that she was probably going to burn through her in-game assets much quicker than others may, especially with recent changes to make critters harder to catch. Another friend has a condition which means that that she is unable to walk easily. Despite living right in the city, the whole mechanic of walking around to find specific Pokémon, or to hatch eggs is totally inaccessible to her. Others have reported frustrations due to the fine motor controls required – throwing is a precise action not suited to those with less coordination or no ability to use their hands. And how about visually impaired users? It now started to feel like many more than rural Suffolk-dwellers were being deliberately excluded (and monetised) due to their circumstances.

Reading up on this, a lot has been made of this in the press, with articles including how black neighbourhoods have fewer interaction points, and questioning whether the game is just for urban elites. Disabilities have been discussed, as well as numerous other negative stories around Pokémon-related accidents and deaths, and the poor placement of certain locations.

The problem seems to stem from the data. As has been widely discussed, the locations in-game have been derived from a previous Niantic game, Ingress. Whilst there is indeed a rich data set, it by no means necessarily matches the differing needs of both audiences. Ingress suspended the ability to submit new locations in September 2015, and whilst it appeared to be fleetingly possible to request new Pokéstop/Gym locations, this was also removed rapidly.

Good data, bad data

For many, the most worrying thing about this game (and many other free services like it), is around our personal data being given away too freely as payment. Whilst this is a troubling trend that affects far more than just the world of Pokémon, this article however shows the potential power of users capturing and sharing mass data through means such as AR games. It discusses how Pokémon Go not only helps to illustrate many of the gaps in our existing data infrastructures, but shows how collaboratively maintained shared data sets could be of benefit across society more broadly:

“A road found by a Pokémon Go player will be available to a car driver using Google Maps to find their way around a strange city. Players in one game can mark an area as out of bounds and players in other games will receive the same warning. Data about a new restaurant will be available to every service whether it be a game or an AR service that tries to entice you into that restaurant.

If the data is handled carefully, and privacy and openness are brought together to build trust, then perhaps some of the camera images could also be incorporated. Perhaps Pokémon Go could automatically spot and report a pothole caught on your camera whilst you were playing the game. People are more likely to trust uses of their data that respect their privacy and benefit society. This trust can lead to increased use of the AR service benefiting the service provider.”

I’d like to see this, and I would strongly welcome the ability to allow the gameplayers to not only influence the mechanics by improving locations, but to contribute to the wider potential. One of my favourite things about Pokémon Go is that I’ve found some interesting stories behind places that I’d previously never noticed, and I’d love for these to grow. We have a church in the village that has notable facets, plus two ancient shops, and a pub that has an excellent back-story (involving a lion) – stories that would be great to surface through an exploration app and potentially more widely.

But all of this is kind of the point, right? This is the game that they want to make, not what we want. One of its goals appears to be around getting able-bodied, mobile people more active, and Niantic have chosen to monetise it how they have. And it’s been a hugely popular. Ultimately these concerns will all inevitably be forgotten in time; overshadowed the meteoric success that the app has enjoyed, but as people who work in digital, we should observe and consider these problems whenever they arise and become debated in society, because they can hold valuable lessons. We can read between the lines and take our learnings into making better products and services ourselves.

Learning lessons

Don’t knowingly sideline certain audiences

When we create digital experiences, we should consider accessibility in the broadest sense, making sure that our baseline experience is the same for everyone, no matter their geography, skill level, or access to connectivity. In this instance, to improve the accessibility of core game mechanics perhaps Pokéballs and potions (giving Pokémon health to fight rival teams in Gyms) could be slowly replenished over time, even at a rate of 1 per day, with more powerful Ultraballs (higher catch rate, currently unavailable to purchase) being the up-sell rather than the core items. This would still favour those with more disposable income being able to stock up, but doesn’t remove the potential for everyone to play.

Ensure you’re using standard accessibility options

With a foray into the world of AR the lines between digital accessibility and physical accessibility start to blur. Whilst it’s important to consider how users may interact with our creations through means other than touch and sight, it’s also vital to think about whether you’re making assumptions around default capabilities. If a core premise is that people need to walk, is there a way of making certain features more accessible to those less able to get out and about – whether through their geography, physical or mental situation, age, or safety?

Consider your responsibilities

What’s the price of you having an easier development life, or making more money? Are you actually exploiting people due to their situation or default privileges? Maybe this is important to you, and maybe it isn’t, but it’s something that you should definitely discuss and make sure you’re comfortable with.

Enhance capabilities rather than blocking usage

The game’s over-reliance on connectivity is something that perfectly illustrates the lack of an accessible baseline for technical reasons rather than situation, yet the two are often inter-linked. Maybe your user is in Suffolk. Maybe a local mast is down. Maybe they’re abroad, on totally different networks to you. Or maybe they have limited data and won’t have any more for a while. This is something that we see again and again, and to me, often can be a red flag for wider issues with the project, huge assumptions, and a lack of user understanding.

Perhaps with Pokémon Go there could have been a very basic set of offline capabilities, allowing those without internet access (due to choice or situation) to continue to open and engage with the app in some form, even if more complex actions do require data and callbacks to a server.

Listen to users, be aware of differences, beware assumptions

Ingress is not Pokémon Go. The audiences aren’t the same, whilst it’s understandable that the rich data gathered through one exercise would be valuable to another, different personas, usage patterns, and testing should have been considered in order to build on top of this, and to make it more rich and appropriate – in the vein that we can see from the article around shared data.

Niantic clearly don’t have the resources or desire at the moment to change this, and to make changes more in line with what their players are asking for. This is another valuable lesson for businesses – consider not only your capabilities and ability to serve the users you’re creating for once your digital creation is unleashed, but also the channels and interaction methods that these services will take. You should also take care to create an architecture which is robust, but flexible enough to make changes – there’s no point in receiving valuable feedback that you want to act upon, but where your hands are tied from self-imposed restrictions and limitations. Ensure that your technical scoping won’t limit you in the future.

Read more from the blog

Back in time:

Tech Talk at West Thames College

Forward in time:

net Magazine issue 286 – Exchange part one

Sally Lait

Sally Lait